Note: The following is the script for one of my YouTube videos. You can watch it here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NfU8mt6iG9g&t=34s

Why Heinrich von Treitschke was popular

in his time is a mystery to me. I mean, granted, his writings are

kind of mesmerising in their own way, like a car crash you can´t

take your eyes off, if you´ll forgive the criminally cliché

comparison – I´m not that imaginative.

But yeah, this guy´s opinions were

pretty damn stupid.

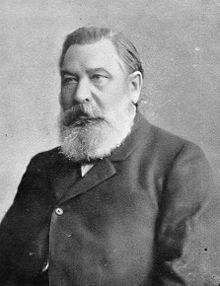

Heinrich von Treitschke in his later years. Source: https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heinrich_von_Treitschke

Before we get to his views, however,

let me fill you in on this interesting fellow´s backstory – in

case you don´t know it yet.

Heinrich von Treitschke was a German

historian, journalist/essayist and member of parliament who lived

from 1834 to 1896. Born into a family with a strong military

background, he was originally a liberal, and an opponent of the

radically consrvative Prussian chancellor, Otto von Bismarck. But his

180-degree political pivot came with the success of Bismarck´s

militarist policies, as three victorious wars against Denmark,

Austria and France led to the establishment of a unified Germany with

Prussia at its head as a new major European power.

Von Treitschke´s newfound passion for

the military shines through with glaring brightness in his work. In a

moment he had been transformed from a progressive to an ardent

nationalist and monarchist with a heartful of love for war and a

scornful disdain for all nations except the German one.

In 1871 he entered the German

Parliament as an MP for the National Liberal Party.

So now that we´ve got his personal

details out of the way, let´s get to the subject of this video –

his political philosophy. The man was a widely-recognised

intellectual, after all. So I read Chapter 1 of his book „Politics“,

which is a collection of lectures published in 1911. In this chapter,

he outlines his theory of a state. Let´s delve right in as I

summarise what I found out about his ideas.

Von Treitschke sees a state as a people

legally united as an independent entity, which is a phrase he repeats

several times throughout the chapter. This carries several

implications with it. Firstly, it means a rejection of the

Enlightenment idea of „Natural Law“, i.e. rules of government

derived directly from reason and therefore universal. Von Treitschke

emphasises the individual differences between all states, which are

necessary because of the differences in the characters of the various

peoples.

However, according to this book, there

are certain rules which hold true everywhere, throughout history. One

such rule is that societies naturally tend towards aristocracy as

opposed to other forms of government. Von Treitschke explains this by

saying that people are naturally different, and therefore inequality

among them is natural, and therefore systems of government based on

inequality are natural. No society, he maintains, can exist which is

not divided into classes. You can see why this guy was vehemently

opposed to social democracy.

And it´s not just within countries

that inequality is inevitable. Although Treitschke does remark that

all people are brothers, as they are all made in God´s image, he

goes on to use the natural inequalities between people to explain,

this time, „the subordination of some groups to others“. This, of

course, fits nicely with his expressed desire to see Germany acquire

its own colonies overseas. He also asserts that each nation deserves

what it gets, meaning that if one country is subjugated by another,

it´s the subjugated country´s fault for being too weak to defend

itself.

As to the functions of the state, von

Treitschke sees its main purposes in, firstly, the administration of

justice and, secondly, war. However, it is clear that its functions

are not limited to these two aspects, since elsewhere he

refers to another one, namely the „duty to stand above social

antagonisms“ (p.53). Here he takes a view similar to Thomas

Hobbes´s justification of a strong state as a peacekeeper among

fundamentally immoral men. Von Treitschke believes that the conflicts

which invariably arise within societies would lead to aggression,

violence and the destruction of society if not for the state, which

is there to protect the rights of the people.

But there´s no reason to be afraid

that the state could ever disappear, because according to the book, a

community of people without a state is impossible. States arise from

human communities as naturally as does language. Here we see an

unmistakeable Aristotelian influence, since Aristotle also believed

that a human community naturally and necessarily forms a polis.

Indeed, von Treitscke draws heavily on

Aristotle, and goes so far as to call Aristotle´s book „Politics“

the greatest work of political science in history. This places him

squarely within the realm of what is called „classical political

philosophy“, a school of thought which goes back largely to the

ancient Greek thinker.

Another attribute of classical

political philosophy is the previously indicated belief that human

beings are inherently flawed, and the state is therefore needed to

overcome the faults in their character. But besides ensuring law and

order, this also means actually making its citizens into better

people. The state plays a major role in the moral development of its

citizens. In fact, von Treitschke goes so far as to write that

writers can only be great if they draw directly from the culture of

their respective nations. This is summed up in the statement that a

great writer must be „a microcosm of his nation“.

This subtly plays in to the statement

by Fichte, quoted elsewhere in the book, that the only way for an

individual to achieve immortality is to embed himself in the

collective memory of his own nation.

As you may have noticed, von Treitschke

is very fond of nations, which is why he rails against both

internationalism, which he sees as lunacy because, as previously

mentioned, each nation has it own character, and provincialism, which

he sees as obsolete, primitive small-mindedness which leads to

intellectual stagnation.

But back to the state. Von Treitschke

identifies a further core aspecct of the state as an intolerance

towards any power above it. According to him, the essence of the

state is power, much as the essence of religion is faith and the

essence of family is love. Since the sovereignty of a state depends

on no other power being able to challenge its authority, von

Treitschke does not consider any state which is not the most powerful

entity on its territory a state in any real sense. Similarly, a state

that cannot wage war because it has no military is not really a

state, since it has no true authority.

Von Treitschke is actually a huge fan

of war, arguing that human greatness andprogress is fueled by

competition among nations, and reinvigorates the character of a

nation which has descended into decadence. He writes:“Misfortune is

a tonic to noble nations, but in continued prosperity even they run

the risk of enervation.“

He sees war as something noble,

claiming that it is typically fought not for material gain, but for

the sake of inherited national honour.

In light of all this, I was surprised

to find that he was not actually advocating for a totalitarian state.

The state von Treitschke wants would be militarist and autocratic,

but there would still be plenty of areas in its citizens´ lives in

which it would not interfere. On p. 25 he writes that „As it aims

only at forming and directing the surface of human existence, it can

everywhere take up an attitude of indifference towards the

conflicting schools of thought in Art, Science, and Religion. It is

satisfied so long as they keep the peace.

So that´s Heinrich von Treitschke for

you. I have to say, some of what he outlines in his lectures seems

quite reasonable, but there´s also a lot of nonsense in the mix

which really kills it for me. Often, he´ll acknowledge an exception

to one of his rules which is so huge that, to me, it disproves the

rule. For example, he writes that small states cannot defend their

sovereignty against large ones, and admits that Switzerland, the

Netherlands and Belgium are exceptions to that rule. That´s three

states in Central Europe alone! Also, for all his insistence that

political science ought to rely on historical observations rather

than armchair philosophy, he provides next to no hstorical evidence

for outrageous claims like war contributing to the moral edification

of a society.

In short, I´m not a fan.

Comments

Post a Comment